How our public spaces can be safer and more welcoming for children

A Georgia mother was recently arrested for reckless endangerment after her 10-year-old son was seen walking outside alone. The warrant for her arrest claimed she “willingly and knowingly” endangered her son’s safety.

The boy had walked less than one mile into town to visit the local dollar store. Despite the boy’s evident ability to navigate public spaces independently, a passerby perceived his presence on the street as alarming and called the police.

This incident illustrates the damaging effects of “safetyism,” a societal anxiety that wrongly assumes children should not be out on their own. Such perceptions not only curtail children’s independence but also perpetuate unnecessary interventions that undermine the ability of parents to make decisions for their own family.

A focus on safetyism ignores the absence of child-friendly infrastructure in many of our towns and cities. For example, many suburban neighbourhoods in North America lack sidewalks and other pedestrian infrastructure. In the Georgia incident, the road the boy walked along did not have a sidewalk, meaning he had to walk on the shoulder. This lack of space exacerbates fears of children being in public spaces alone.

How did we reach a point where parents now risk arrest if their children are seen outside alone?

Rise of safetyism

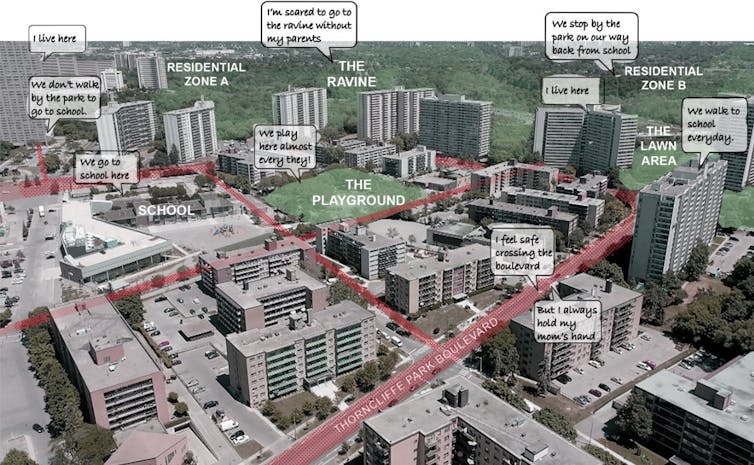

My research focuses on how public spaces can be better designed for children. As societies change, their understanding of childhood changes. The way children were treated 50 years ago differs from what they are experiencing now. Likewise, perceptions of what is safe to do and what is not have also changed over time.

Spontaneous outdoor play is a vital way for children to explore, grow and understand their environment. Yet, urban and suburban design often stifles this natural inclination. These environments usually confine children’s play to parks and playgrounds while leaving broader public spaces off-limits.

Historically, attitudes toward children in public spaces have been shaped by industrialization, rapid urbanization and the growth of suburbs. Early playgrounds emerged during the child-saving movement of the 1980s, aiming to protect children from street dangers.

However, these heavily supervised, segregated spaces reflected societal biases, dividing children by race, gender and class. Activities prepared boys for leadership, girls for motherhood, and marginalized children for labour.

Architects and planners like Aldo van Eyck have challenged these restrictive notions, advocating for adventure playgrounds and child-friendly urban spaces. Their work emphasizes unstructured play that promotes children’s agency.

Despite these efforts, the rise of safetyism in recent decades has eroded children’s independence. Fears of busy traffic and stranger dangers have led caregivers to limit children’s exposure to the outdoors. This “bubble-wrapped generation,” as education professor Karen Malone describes, experiences childhood within narrowly defined boundaries, chauffeured between organized activities.

This overprotection deprives children of opportunities to develop resilience. Car-dependence also contributes to the very risks it seeks to prevent. For instance, traffic congestion caused by parental drop-offs near schools increases accident risks. Meanwhile, children shielded from navigating public spaces may lack the skills to handle unexpected situations, such as how to seek help when lost.

The Georgia incident starkly illustrates how societal attitudes perpetuate these cycles. The passerby’s decision to involve the police reflects a broader societal discomfort with children’s presence in public spaces. Addressing this issue requires both cultural and infrastructural change.

Child-friendly cities

It is time for a new child-saving movement. Cities like Barcelona and Copenhagen offer inspiring examples of child-friendly design that challenge these anxieties. The walkability of these cities contributes to children’s overall skill development.

Integrating playful elements along walkable pathways further advances opportunities to explore and develop a sense of safety and belonging. These opportunities normalize children being in public spaces, countering the harmful perceptions that fuel safetyism.

Implementing traffic-calming measures is another way to foster safer pedestrian movements around the neighbourhood. Among these measures are lowering speed limits around the residential buildings, adding more intersections with signals and mid-block crosswalks especially along the longer and curved streets.

Walkability can also be improved by implementing soft edges along pathways. As opposed to hard physical boundaries such as fences, incorporating soft edges, such as green buffers ensure the safety of children and pedestrians while still enabling them to freely navigate space and engage in playful activities.

Moreover, the creation of intergenerational public spaces must be prioritized over creating age-specific spaces, such as the common fenced playgrounds. First, being in these spaces encourages a sense of shared responsibility, thus improving children’s agency. Second, they foster a sense of community among all, which eventually improves parental perceptions of safety. Third, intergenerational spaces allow caregivers to socialize while children play. This opportunity is an important time-out for the caregivers, while still being able to supervise their kids.

Children’s well-being is a barometer for the health of our societies and cities. To create inclusive, sustainable communities, we must challenge the restrictive boundaries that confine children’s experiences and see their independence as a threat. By designing child-friendly public spaces we can nurture future generations who are better equipped to navigate our world.![]()

Anahita Shadkam, Sessional Instructor, School of Urban and Regional Planning,, Toronto Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment