Land Use Neighbourhood Community Hub

Launch stands for Land Use Community Neightbourhood Hub. The purpose is to provide residents in Kitchener with information and links to issues of development that affect them.

Sunday, November 30, 2025

Housing, Human Rights and the City of Kitchener

by Peter Eglin

These were the refrains echoing in my mind watching and discussing UW Planning Professor Brian Doucet’s outstanding film on Canada’s housing crisis Thinking Beyond the Market shown at the Princess on November 16 care of Waterloo MPP Catherine Fife (Brian Doucet Waterloo Region Record November, 10, 2025). Rather than bemoaning the federal and provincial governments’ disgraceful failure since the mid-1990s to house their citizens adequately despite 77 years of high-minded declarations to do just the opposite, Doucet takes his audience on a country-wide tour of ordinary people’s successful efforts to get local governments, charities and non-profits to build and to defend truly affordable housing, “affordable” being 30% of before-tax income (not the 80% of market value beloved of developers and their political friends). As a result we have all come to know what “renoviction” and “demoviction” mean.

Housing, after all, is first and foremost a human right before it is an investment commodity.

In the case of Metro Vancouver a section of the film is devoted to a remarkable partnership among three first nations and the City to develop a sizeable parcel of land in conformity with indigenous principles.

In Kitchener we could go a step further. Certainly, the City could take up available government land on which to build affordable housing. But if, as in Toronto (Toronto Star November 17, 2025), about 20 percent of approved projects are idle with vacant lots, while here 2,300 people are homeless, about 1,000 sleeping rough, let the City acquire those lots to build such housing with partners such as Indwell (also featured in Doucet’s movie), taking advantage of federal and provincial government programs.

What? Deprive private investors of their failing investments? Interfere with the market? Are you mad?

The Court’s judgment re 100 Victoria Street invoked s.7 of the Charter asserting the right of encampment residents to life, liberty and security of the person. That’s like saying it would be a crime against humanity for them to be evicted. And that’s like saying that members of Council need to consider the message they are sending to their constituents, the common people of Kitchener who elected them.

Councillors that I noticed at the showing were the Region’s Erb, Huinink and Rodrigues, Waterloo’s Hamner, Roe, Vasic and Wright and Kitchener’s Chapman flying solo. Given that the concept of democracy means rule by the common people (the “demos”), we commoners clearly have our work cut out for us if Kitchener is ever to become a place that truly honours the human right to housing of its residents.

By permission of the author. Also published in the Waterloo Region Record, November 26, 2025

Tuesday, November 18, 2025

Guide to Renewable Energy and Battery Storage Projects

In less than a decade, renewable energy has brought substantial financial benefits to Alberta landowners and communities, while also generating affordable energy for the province's electrical grid. Given that renewables generate the lowest-cost form of new energy available, new project proposals are sure to continue to arise. But when landowners and communities are first approached by wind and solar developers as potential hosts for a renewable energy project, it naturally generates a lot of questions.

Our new publication, Guide to Renewable Energy and Battery Storage Projects: How Alberta landowners can reap the benefits of hosting clean energy, takes care of a lot of the research and homework they would otherwise face. The guide starts by grounding readers with an explanation of what renewable energy is and how the industry has evolved in Alberta in recent years. It outlines the benefits of wind and solar projects, and the potential impacts.

Tuesday, October 7, 2025

Dense, compact urban growth is favoured by mid-sized Canadian cities

Canada’s mid-sized cities — those with populations between 50,000 to 500,000 — have long been characterized as low-density, dispersed and decentralized. In these cities, cars dominate, public transit is limited and residents prefer the space and privacy of suburban neighbourhoods.

Several mounting issues, ranging from climate change and the housing affordability crisis to the growing infrastructure deficit, are challenging municipalities to rethink this approach.

Cities are adopting growth management strategies that promote density and seek to curtail, rather than encourage, urban sprawl. Key to this is intensification, a strategy that prioritizes adding new housing in existing and mature neighbourhoods instead of outward expansion along the city’s edge.

City centres are often central to intensification strategies, given the abundance of vacant or underused land. Adding more residents supports downtown revitalization efforts, while simultaneously curbing urban sprawl.

Challenges of intensification

Despite the adoption of bold policies, our research shows that implementation remains a challenge. In 2013, Regina set an intensification target requiring that 30 per cent of the housing built each year would be located within the city’s mature and established neighbourhoods. But between 2014 and 2021, the target was missed each year, and almost all growth occurred at the edge of the city in the form of new suburban development.

This disconnect is not particularly unique and is often referred to as the “say-do gap,” where development outcomes differ from intentions. This presents real challenges for cities trying to shift away from low-density suburban growth towards higher-density development.

Because Canada is a suburban nation, dense and compact mid-sized cities are atypical. A series of barriers further entrench this, including low demand for high-density urban living, difficulties in assembling land, aging infrastructure and overly rigid planning rules and processes that stifle innovation.

The failure to implement higher-density development raises the question: is intensification in mid-sized cities more aspirational than viable?

Success stories

Several mid-sized cities have experienced recent success with intensification. This has been marked by a flurry of downtown development activity, including new condos and rental towers.

Between 2016 and 2021, the number of downtown residents in Canadian cities increased by 11 per cent, exceeding the previous five-year period of 4.6 per cent.

Among the success stories is Halifax, which had a 25 per cent increase — the fastest downtown growth in Canada. Kelowna was not far behind, with a 23 per cent increase in its downtown residential population.

Other mid-sized cities, including Kingston, Victoria, London, Abbotsford, Kamloops and Moncton, also experienced above-average growth over this period.

Evolving downtowns

This growth can be attributed to several factors, one of the most important being downtown livability: the presence of amenities and services that meet the needs of residents. Many downtowns have evolved to cater primarily to the needs of daytime office workers at the expense of residents, who live — or might like to live — downtown.

Kelowna, however, offers an alternative experience shaped by intentional efforts to make the downtown friendly to residents. Restaurants and cafes line the streets, mixed among services including medical offices, fitness studios and even a full-service grocery store, a rare find in a mid-sized city as many downtowns have become food deserts.

Cultural and civic amenities, including the central library, city hall, museums, galleries and entertainment venues — including a 7,000-seat arena — are downtown. The downtown also borders Okanagan Lake, offering access to recreational and natural amenities. Beyond convenience, the mix of amenities and services in Kelowna makes for a vibrant downtown, which is key to increasing the appeal for downtown living.

Other cities can take inspiration from Kelowna by re-imagining and reshaping the downtown as a vibrant urban neighbourhood — and not solely as a place where people come to work. Municipalities can complement these efforts by reforming overly complex and rigid regulations that impede intensification — not just downtown, but in other neighbourhoods too.

Reforming and clarifying regulations

Our research shows that while many developers support intensification in principle, they often favour low-density suburban development because it provides more predictable returns and approvals processes than downtown mixed-use developments. Many developers also lack the expertise to take on these more complex and riskier projects.

Unsurprisingly, developers in mid-sized cities want the same things as those in larger cities: clearer rules, faster approvals and financial incentives to build denser development in the locations planners are calling for, like downtowns. While developers have long advocated for these changes, governments are now responding with greater urgency.

The housing accelerator fund, introduced by the federal government in 2023, provides municipalities with millions in funding to support housing construction. In exchange, municipalities have reformed zoning regulations, introduced fiscal incentives and expedited the approval process.

In British Columbia, provincial legislation was introduced to permit up to four housing units on parcels that previously only allowed detached or semi-detached dwellings, and up to six units of housing on larger lots in residential zones near transit. The requirement for site-by-site public hearings has also been removed.

In B.C.’s larger cities, legislation was introduced to remove parking minimums and permit taller buildings and increased housing densities around transit hubs.

Regulatory reforms and improved approval processes aim to streamline development. While these are important changes in making mid-sized cities denser and more compact, the gap between planning ideals and market realities remains wide.

A major factor is opposition from residents and councillors, who frequently resist dense development because of perceptions and concerns about increased noise and traffic and lowered property values. This suggests there is work to be done beyond downtown investments, and regulatory and approval reforms to further facilitate intensification.

Changing cities

Nonetheless, the surge of recent development activity and downtown population growth — in Halifax, Kelowna and elsewhere — reflect important milestones in the evolution of mid-sized cities.

This signals a notable departure from the longstanding narrative that frames these cities as low-density with depleted downtowns.

Recent developments give reason to be cautiously optimistic about a future where Canada’s mid-sized cities become denser and more compact, and with vibrant and liveable downtown cores.![]()

Rylan Graham, Assistant Professor, University of Northern British Columbia and Jeffrey Biggar, Assistant Professor, Planning, Dalhousie University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, September 23, 2025

Turning houses into homes: Community land trusts offer a fix to Canada’s housing crisis

Imagine if every time a hospital was built, it came with an expiry date. Twenty-five years later, it would be sold to the highest bidder and patients would be told to find care elsewhere.

This is unthinkable in health care, yet this is precisely how we treat affordable housing in Canada. Government programs provide funding for the construction of affordable housing, but without long-term commitments to ensure those same housing units remain affordable.

As the federal government puts the finishing touches on planning its new housing programs, we must ensure that affordable housing stays affordable for generations.

Governments pour billions into new housing programs, but the homes that are built aren’t required to remain affordable over the long term, meaning they often slip back into the speculative market after just a few decades.

Government programs subsidize the capital costs of housing construction, with rent affordability guaranteed for a limited period (usually 10-20 years). A recent study found that Canada lost 10 affordable housing units for every new one built over a decade.

The implication is that land is a tradeable asset as governments forget it’s also the foundation for homes, communities and stability. If governments are serious about solving the housing crisis, they must change that.

Canada has done it before. In the 1970s and ’80s, governments invested heavily in co-operative housing, creating tens of thousands of permanently affordable homes that continue to serve communities today. Those investments prove what’s possible when land and housing are treated as long-term public goods rather than short-term commodities.

Holding land in perpetuity

Community land trusts (CLTs) are the next generation of that vision. They extend the principle of permanence to a wider range of housing types, neighbourhoods and community uses, ensuring that affordability and stability are not just won but protected for generations.

A new report by my UBC colleague, Kuni Kamizaki, entitled A Case for Community Land Trusts in Canada: Promising Community Practices and Public Policy Options, shows how CLTs can reframe the housing conversation in creating a long-term, affordable housing stock. It’s not simply about how many homes we build, but who controls the land beneath them.

CLTs are membership-based, non-profit organizations that acquire and hold land in perpetuity for community benefit. People then purchase long-term leases in individual units.

This means that the land is removed from speculative markets, stewarded democratically and the housing is locked in as affordable, often for 99 years or more. Unlike situations where properties are sold and affordability disappears after 10 to 25 years, CLTs preserve it permanently.

This is not a distant dream. Kamizaki identifies roughly 45 CLTs operating or forming across Canada, more than 60 per cent of them launched in the last five years. They range from the Community Land Trust Foundation of BC to Toronto’s Parkdale Neighbourhood Land Trust, each committed to collective ownership, community governance and significant affordability.

Meeting local needs

CLTs flip the switch on the usual policy logic. Too often, publicly owned land is sold to private developers, representing — as Kamizaki puts it — “a long-term loss of public good and a lost opportunity to build non-market housing with deep affordability.”

Once sold, the land is gone, along with the chance to secure permanent affordability. CLTs keep that land in community hands, using it to meet local needs rather than feed speculative demand.

The benefits go beyond economics. CLTs can advance reconciliation and racial justice by challenging the real estate practices that have displaced racialized communities for decades. This treats land as a relationship rather than a commodity, an understanding rooted in stewardship, responsibility and belonging. In other words: turning housing into homes.

Vancouver’s Hogan’s Alley Society shows this potential in action. Once home to a thriving Black community, the neighbourhood was demolished in the 1970s in the name of urban renewal. The organization is now working to reclaim that land through a CLT, rebuilding a Black cultural hub grounded in long-term stewardship and land-back principles. This is housing justice intertwined with cultural restoration.

But CLTs cannot expand on good will alone. The National Housing Strategy Act recognizes housing as a human right, yet Canadian policies still treat it as a market commodity first and a necessity second.

Market-based “solutions” inevitably recreate the same conditions — speculation, gentrification, displacement — that produced the crisis.

How to advance CLTs

Kamizaki’s report outlines several steps governments can take to make CLTs a central part of Canada’s housing strategy, including the following:

- Prioritize permanent affordability over short-term targets;

- Support CLTs led by racialized and marginalized communities as acts of reparation;

- Transfer public land into community hands;

- Create legal frameworks tailored to CLTs;

- Provide stable funding and technical support through a national CLT hub.

These are structural commitments that address the core questions: Who owns land? Who decides how it’s used? Who benefits from public investment?

CLTs answer these questions by matching the permanence of the right to housing with the permanence of land stewardship. They take the volatility of the market out of the equation and put democratic decision-making into the hands of the people who live in and care for their communities.

Many studies reinforce the conclusion that CLTs deliver lasting affordability, protect against displacement, and strengthen community ties. The real question is whether Canada has the political will to embrace them.

The housing crisis is urgent, and so is the opportunity. We can keep funding market Band-aids that expire in a generation, or we can take land off the speculative market, put it in community hands and make houses into homes. For good.

Alexandra Flynn, Associate Professor, Peter A. Allard School of Law, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Monday, September 22, 2025

Canadian cities can prepare for climate change by building with nature

The housing affordability crisis is top of mind for many around the world, including Canadians. Between 2019 and 2024, house prices in Toronto and Montréal had an average annual increase of 6.7 per cent and 10.2 per cent, respectively.

Prices throughout the country are expected to continue increasing over the next decade and as a result, the pressure is intense to rapidly increase residential development.

Yet, municipal governments must balance this pressure with other tasks, like preparing for the effects of climate change. Some of the most pressing challenges for cities include meeting their housing and climate change goals without massive changes in land use to maintain green spaces and the benefits they provide to people.

Natural spaces like parks and woodlands provides many diverse benefits to city residents, from helping to cool off surrounding neighbourhoods to providing recreational areas.

The advantage these spaces have over grey infrastructure is that they can simultaneously help combat multiple challenges faced by cities, including poor air quality, heatwaves and flooding. When nature is intentionally used to combat these types of challenges, it is referred to as nature-based solutions.

Nonetheless, nature-based solutions are still rarely implemented in developments. Therefore, it’s important to identify and use key opportunities that can help communities balance their competing goals by increasing the use of nature-based solutions.

By highlighting these opportunities, we can inform municipal governments, developers and residents about how communities can be built to successfully combat climate change and other challenges.

In our recent study, we interviewed planners and developers throughout Ontario to identify these opportunities.

Nature in development

Municipal planners and private land developers across Ontario are obliged by provincial policy to consider nature in their decisions about the planning and development of neighbourhoods.

However, this largely happens because they are required by law to protect municipal natural heritage systems (large woodlots or wetlands, for example), and not because they understand or support the benefits from nature, such as flood prevention.

Natural features that fall outside the natural heritage system, such as smaller woodlots or individual trees, are not protected by provincial policy. Instead, they can be protected by municipal policy or bylaws. However, these policies and bylaws vary, and some municipalities do a better job than others in protecting nature for their residents.

Developers often see protected nature as a barrier to development, but some of them also understand that it provides benefits to residents. Some try to make use of nature in innovative ways, like building natural pathways or naturalized creeks through a subdivision.

Unfortunately, municipalities sometimes push back against these innovations because of concerns over maintenance costs and worries about possible interference with infrastructure.

Nature and climate change

Overall, the planners and developers we interviewed recognized that nature can help communities fight the effects of climate change.

They stated that planning policies and bylaws are also starting to change in ways that can address these concerns. For example, many municipalities have established tree canopy targets or introduced more restrictive stormwater management requirements.

But climate change is rarely stated as the reason for a change to policy and bylaws. For example, a city might recognize tree cover is important for the city environment and introduce a tree protection bylaw, but that does not mean the bylaw addresses climate change.

Similarly, developers might plant trees to beautify a neighbourhood and make it more desirable for home buyers, but they might not do this to reduce climate change impacts. Addressing climate change only implicitly or as a side effect makes it much harder to co-ordinate different actions and can limit their overall effectiveness.

A main reason why the climate change benefits of nature are considered only implicitly is that planners and developers are uncertain about how reliable the information is for quantifying these benefits.

Another problem is that municipalities differ in how they address these issues, which creates highly variable regulatory conditions. Having province- or nation-wide standards would help fix this issue.

Though they are not yet widely implemented across Canada, some municipalities use green development standards as a key mechanism for introducing benefits of nature in developments. These standards work, for example, by mandating a minimum percentage of green landscaping on a development site. Unfortunately, Ontario’s recently passed Bill-17 has created uncertainty around these standards.

Ways to support nature-based solutions

There are key opportunities to support building more sustainable and climate-ready communities through increased use of nature-based solutions in developments. These opportunities largely come through policy, tools and people:

Provincial and municipal policy changes that consider the climate change benefits of nature-based solutions could help increase its use in development. This could be done by strengthening and expanding green development standards, like those currently implemented in some cities.

Developing and using tools that can rigorously quantify the climate change benefits of nature-based solutions could also have substantial impact. These tools could clarify the benefits of nature-based solutions and provide a solid argument for their increased use.

Collaboration between the public and private sectors is crucial to encourage increased use of nature-based solutions. Whether it is working together to craft realistic policy goals or to incorporate new tools, both sectors are key to ensuring changes are effective and efficient.

Adam Skoyles, PhD Candidate, School of Planning, University of Waterloo and Michael Drescher, Associate Professor, School of Planning, University of Waterloo

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, August 22, 2025

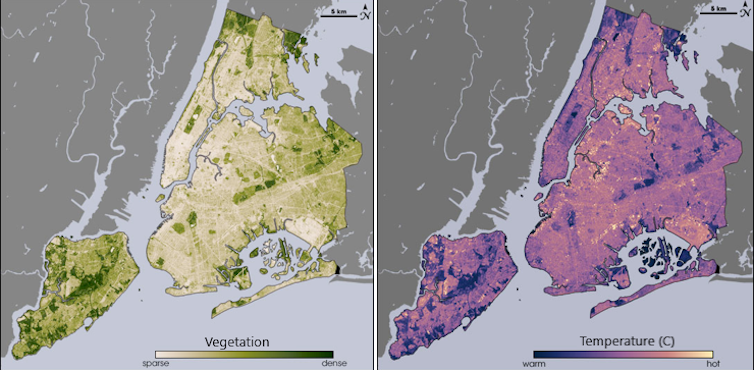

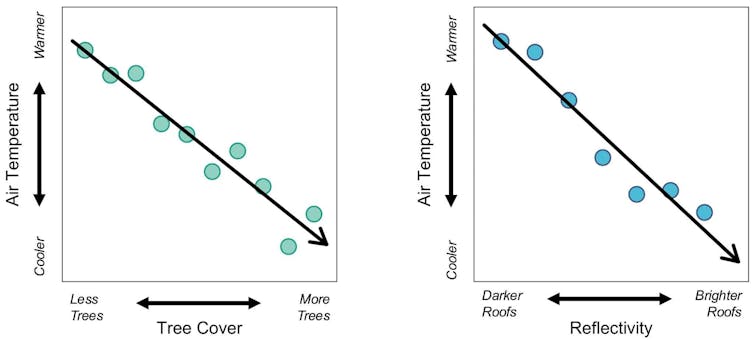

Arbres urbains ou toitures réfléchissantes : quelle est la meilleure solution pour les villes afin de lutter contre la chaleur ?

Lorsque la chaleur estivale s'installe, les villes peuvent commencer à ressembler à des fours, car les bâtiments et les chaussées emprisonnent la chaleur du soleil, tandis que les véhicules et les climatiseurs rejettent davantage de chaleur dans l'air.

La température dans un quartier urbain dans lequel il y a peu d'arbres peut être supérieure de 5,5 degrés Celsius à celle des quartiers voisins. Cela signifie que la climatisation fonctionne davantage, mettant le réseau électrique à rude épreuve et exposant les habitants aux pannes de courant.

Il existe des mesures éprouvées que les villes peuvent prendre pour rafraîchir l'air, par exemple planter des arbres qui fournissent de l'ombre et de l'humidité, ou créer des toitures réfléchissantes qui réfléchissent le rayonnement solaire vers l'atmosphère au lieu de l'absorber.

Mais ces mesures sont-elles efficaces partout ?

Nous étudions les risques liés à la chaleur dans les villes en tant qu'écologistes urbains, et analysons l'impact de la plantation d'arbres et des toitures réfléchissantes dans différentes villes et différents quartiers. Nos conclusions peuvent aider les villes et les propriétaires à mieux cibler leurs efforts pour lutter contre la chaleur.

Cet article fait partie de notre série Nos villes d’hier à demain. Le tissu urbain connait de multiples mutations, avec chacune ses implications culturelles, économiques, sociales et – tout particulièrement en cette année électorale – politiques. Pour éclairer ces divers enjeux, La Conversation invite les chercheuses et chercheurs à aborder l’actualité de nos villes.

La magie des arbres

Les arbres urbains offrent une protection naturelle contre la hausse des températures. Ils apportent de l'ombre et libèrent de la vapeur d'eau par leurs feuilles, un processus similaire à la transpiration humaine. Cela refroidit l'air ambiant et atténue la chaleur de l'après-midi.

L'ajout d'arbres dans les rues, les parcs et les jardins résidentiels peut changer sensiblement la température ressentie dans un quartier, les quartiers arborés étant près d'1,7 °C plus frais que ceux qui le sont moins.

Mais planter des arbres n'est pas toujours simple.

Dans les villes chaudes et sèches, les arbres ont souvent besoin d'être irrigués pour survivre, ce qui peut mettre à l'épreuve des ressources en eau déjà limitées. Les arbres doivent survivre pendant des décennies pour atteindre une taille suffisante afin de fournir de l'ombre et libérer assez de vapeur d'eau pour réduire la température de l'air.

Les coûts d'entretien annuels, estimés à environ 900 dollars américains annuels par arbre à Boston, peuvent dépasser l'investissement initial de plantation.

La difficulté, c'est que les quartiers urbains denses, où la chaleur est la plus intense, sont souvent trop encombrés de bâtiments et de routes pour permettre la plantation d'arbres supplémentaires.

Comment les toitures réfléchissantes peuvent aider pendant les journées chaudes

Une autre option consiste à recourir aux toitures réfléchissantes. Recouvrir les toitures d'une peinture réfléchissante ou utiliser des matériaux de couleur claire permet aux bâtiments de réfléchir davantage la lumière du soleil vers l'atmosphère au lieu de l'absorber sous forme de chaleur.

Ces toitures peuvent réduire la température à l'intérieur d'un immeuble sans climatisation d'environ 1 à 3,3 °C et peuvent réduire la demande maximale de climatisation jusqu'à 27 % dans les bâtiments climatisés, selon une étude. Elles peuvent également procurer un rafraîchissement immédiat en réduisant les températures extérieures dans les zones densément peuplées. Les coûts d'entretien sont aussi plus faibles que ceux liés à l'expansion des forêts urbaines.

Cependant, tout comme les arbres, les toitures réfléchissantes ont leurs limites. Elles sont plus efficaces sur les toits plats que sur les toits en pente recouverts de bardeaux, car les toits plats sont souvent recouverts de caoutchouc qui emprisonne la chaleur et sont exposés à un ensoleillement plus direct l'après-midi.

Les villes disposent également d'un nombre limité de toits susceptibles d'être convertis. Et dans les villes qui comptent déjà de nombreux toits de couleur claire, quelques toitures supplémentaires pourraient contribuer à réduire les coûts de climatisation dans ces bâtiments, mais elles n'auraient pas beaucoup d'effet à l'échelle du quartier.

En évaluant les avantages et les inconvénients des deux stratégies, les villes peuvent concevoir des plans adaptés à leur situation pour lutter contre la chaleur.

Choisir la bonne combinaison de solutions de refroidissement

De nombreuses villes à travers le monde ont pris des mesures pour s'adapter à la chaleur extrême, avec des programmes de plantation d'arbres et de toitures réfléchissantes qui imposent des exigences en matière de réflectivité ou en encouragent l'adoption.

À Detroit, des organisations à but non lucratif ont planté plus de 166 000 arbres depuis 1989. À Los Angeles, les codes du bâtiment exigent désormais que les toits des nouvelles constructions résidentielles respectent des normes de réflectivité spécifiques.

Dans une étude récente, nous avons analysé le potentiel de Boston pour réduire la chaleur dans les quartiers vulnérables de la ville. Les résultats montrent comment une stratégie à coût maîtrisé pourrait apporter des bénéfices significatifs en matière de refroidissement.

Par exemple, nous avons constaté que la plantation d'arbres peut refroidir l'air de 35 % de plus que l'installation de toitures réfléchissantes dans les endroits où il est possible de planter des arbres.

Cependant, la plupart des meilleurs emplacements pour planter de nouveaux arbres à Boston ne se trouvent pas dans les quartiers qui en ont le plus besoin. Dans ces quartiers, nous avons constaté que les toitures réfléchissantes constituaient un meilleur choix.

En investissant moins de 1 % du budget annuel de fonctionnement de la ville, soit environ 34 millions de dollars, dans 2 500 nouveaux arbres et 3 000 toitures réfléchissantes ciblant les zones les plus à risque, nous avons constaté que Boston pourrait réduire l'exposition à la chaleur pour près de 80 000 habitants. Cela permettrait de réduire la température de l'air l'après-midi en été de plus de 0,6 °C dans ces quartiers.

Bien que cette baisse puisse sembler modeste, il a été démontré que des réductions de cette ampleur diminuent sensiblement les maladies et les décès liés à la chaleur, augmentent la productivité et réduisent les coûts énergétiques liés à la climatisation des bâtiments.

Toutes les villes ne bénéficieront pas de la même combinaison. Le paysage urbain de Boston comprend de nombreux toits plats et noirs qui ne réfléchissent qu'environ 12 % de la lumière solaire, ce qui rend les toitures réfléchissantes qui réfléchissent plus de 65 % de la lumière solaire particulièrement efficaces. Boston bénéficie également d'une saison de végétation relativement humide qui favorise le développement d'un couvert forestier urbain luxuriant, rendant ces deux solutions viables.

Dans les endroits où il y a moins de toits plats et sombres pouvant être convertis en toitures réfléchissantes, la plantation d'arbres peut apporter davantage de bénéfices. À l'inverse, dans les villes où il reste peu d'espace pour planter de nouveaux arbres ou où la chaleur extrême et la sécheresse limitent la survie des arbres, les toitures réfléchissantes peuvent être une meilleure solution.

Phoenix, par exemple, compte déjà de nombreux toits de couleur claire. Les arbres pourraient être une option, mais ils nécessiteraient un système d'irrigation.

Déjà des milliers d'abonnés à l'infolettre de La Conversation. Et vous ? Abonnez-vous gratuitement à notre infolettre pour mieux comprendre les grands enjeux contemporains.

Apporter les solutions là où les gens en ont besoin

La création de zones ombragées le long des trottoirs peut avoir un double effet en offrant aux piétons un endroit pour s'abriter du soleil et en rafraîchissant les bâtiments. À New York, par exemple, les arbres de rue représentent environ 25 % de la forêt urbaine totale.

Les toitures réfléchissantes peuvent être plus difficiles à déployer pour les autorités publiques, car elles nécessitent la collaboration des propriétaires. Cela signifie souvent que les villes doivent proposer des mesures incitatives. Louisville, dans le Kentucky, par exemple, accorde des rabais pouvant aller jusqu'à 2 000 dollars aux propriétaires qui installent des matériaux de toiture réfléchissants, et jusqu'à 5 000 dollars aux entreprises commerciales dotées de toits plats qui utilisent des revêtements réfléchissants.

De telles initiatives peuvent contribuer à étendre les bénéfices des toitures réfléchissantes dans les quartiers densément peuplés qui ont le plus besoin d'être rafraîchis.

Alors que les changements climatiques entraînent une augmentation de la fréquence et de l'intensité des vagues de chaleur urbaine, les villes disposent d'outils puissants pour faire baisser la température. En prêtant attention à ce qui existe déjà et à ce qui est faisable, elles peuvent trouver la meilleure stratégie en fonction de leurs besoins et de leurs réalités.![]()

Ian Smith, Research Scientist in Earth & Environment, Boston University and Lucy Hutyra, Distinguished Professor & Chair of Earth and Environment, Boston University, Boston University

Cet article est republié à partir de The Conversation sous licence Creative Commons. Lire l’article original.

Monday, August 11, 2025

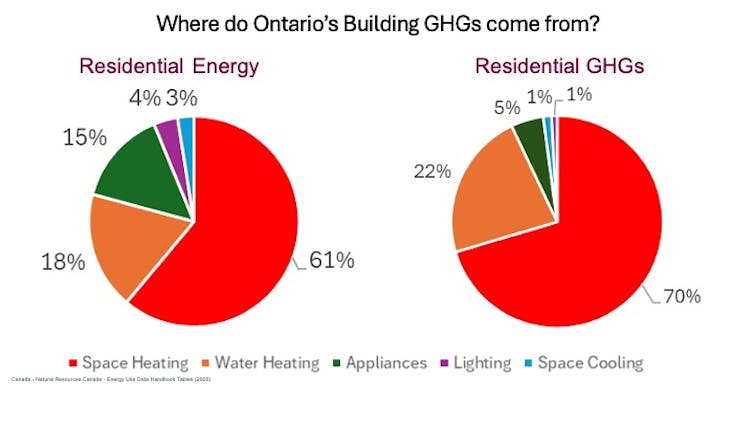

Canada could use thermal infrastructure to turn wasted heat emissions into energy

Buildings are the third-largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. In many cities, including Vancouver, Toronto and Calgary, buildings are the single highest source of emissions.

The recently launched Infrastructure for Good barometer, released by consulting firm Deloitte, suggests that Canada’s infrastructure investments already top the global list in terms of positive societal, economic and environmental benefits.

In fact, over the past 150 years, Canada has built railways, roads, clean water systems, electrical grids, pipelines and communication networks to connect and serve people across the country.

Now, there’s an opportunity to build on Canada’s impressive tradition by creating a new form of infrastructure: capturing, storing and sharing the massive amounts of heat lost from industry, electricity generation and communities, even in summer.

Natural gas precedent

Indoor heating often comes from burning fossil fuels — three-quarters of Ontario homes, for example, are heated by natural gas. Until about 1966, homes across Canada were primarily heated by wood stoves, coal boilers, oil furnaces or heaters using electricity from coal-fired power plants.

After the oil crisis of the 1970s, many of those fuels were replaced by natural gas, delivered directly to individual homes. The cost of the natural gas infrastructure, including a national network of pipelines, was amortized over more than 50 years to make the cost more practical.

This reliable, low-cost energy source quickly proved to be popular. The change cut heating emissions across Ontario by roughly half throughout the 1970s and 1980s, long before climate change was the concern it is today.

Now, as the need to decarbonize becomes more pressing, recent studies not only emphasize the often-overstated emissions reductions benefits from using natural gas; they also indicate that burning this fuel source is still far from net-zero.

However, there’s no reason why Canadian governments can’t invest in new infrastructure-based alternative heating solutions. This time, they could replace natural gas with an alternative, net-zero source: the wasted heat already emitted by other energy uses.

Heat capture and storage

Depending on the source temperature, technology used and system design, heat can be captured throughout the year, stored and distributed as needed. A type of infrastructure called thermal networks could capture leftover heat from factories and nuclear and gas-fired power plants.

In essence, thermal networks take excess thermal energy from industrial processes (though thermal energy can theoretically be captured from a variety of different sources), and use it as a centralized heating source for a series of insulated underground pipelines connected to multiple other buildings. These pipelines, in turn, are used to heat or cool these connected buildings.

A substantial potential to capture heat similarly exists in every neighbourhood. Heat is produced by data centres, grocery stores, laundromats, restaurants, sewage systems and even hockey arenas.

In Ontario, the amount of energy we dump in the form of heat is greater than all the natural gas we use to heat our homes.

A restaurant, for example, can produce enough heat for seven family homes. To take advantage of the wasted heat, Canada needs to build thermal networks, corridors and storage to capture and distribute heat directly to consumers.

The effort demands substantial leadership from all levels of government. Creating these systems would be expensive, but the technology does exist, and the one-time cost would pay for itself many times over.

Such systems are already working in other cold countries. Thermal networks heat half the homes in Sweden and two-thirds of homes in Denmark.

The oil crisis of the 1970s motivated both countries to find new domestic heating sources. They financed their new infrastructure over 50 years and reduced their investment risks through low-interest bonds (loaned by public banks) and generous subsidies.

These were offered to utility companies looking to expand district energy operations, and to consumers by incentivizing connections to such systems. Additionally, in Denmark, controlled consumer prices served a similar function.

At least seven American states have established thermal energy networks, with New York being the first. The state’s Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act allows public utilities to own, operate and manage thermal networks.

They can supply thermal energy, but so can private producers such as data centres, all with public oversight. Such a strategy avoids monopolies and allows gas and electric utilities to deliver services through central networks.

An opportunity for Canada

Canada has a real opportunity to learn from the experiences of Sweden, Denmark and New York. In doing so, Canada can create a beneficial and truly national heating system in the process. Beginning with federal government leadership, thermal networks could be built across Canada, tailored to the unique and individual needs, strengths and opportunities of municipalities and provinces.

Such a shift would reduce emissions and generate greater energy sovereignty for Canada. It could drive a just energy strategy that could provide employment opportunities for those displaced by the transition away from fossil fuels, while simultaneously increasing Canada’s economic independence in the process.

Thermal networks could be built using pipelines made from Canadian steel. Oil-well drillers from Alberta could dig borehole heat-storage systems. A new market for heat-recovery pumps would create good advanced-manufacturing jobs in Canada.

Funding for the infrastructure could come through public-private partnerships, with major investments from public banks and pension funds, earning a solid and secure rate of return. A regulated approach and process could permit this infrastructure cost to be amortized over decades, similar to the way past governments have financed gas, electrical and water networks.

As researchers studying the engineering and policy potential of such an opportunity, we view such actions as essential if net-zero is to be achieved in the Canadian building sector. They are also a win-win solution for incumbent industry, various levels of government and citizens across Canada alike.

Yet efforts to install robust thermal networks remain stalled by institutional inertia, the strong influence of the oil industry, limited citizen awareness of the technology’s potential and a tendency for government to view the electrification of heating as the primary solution to building decarbonization.

In this time of environmental crisis and international uncertainty, pushing past these barriers, drawing on Canada’s lengthy history of constructing infrastructure and creating this new form thermal energy infrastructure would be a safe, beneficial and conscientious way to move Canada into a more climate-friendly future.![]()

James (Jim) S. Cotton, Professor, Department of Mechanical Engineering, McMaster University and Caleb Duffield, PhD Candidate in Political Science, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Friday, July 25, 2025

How women are trapped in years of homelessness that often begin in their teens

Many women without children in their care who become homeless in Canada remain homeless for many years. Yet their experiences remain misunderstood and largely ignored because of the ways we define and measure homelessness in Canada.

I have worked in the women’s emergency shelter system in Hamilton, Ont., since 2012. I have met many women who have been navigating homelessness for years — with no permanent solution to their housing crisis. For my PhD in social work, I interviewed 21 women who had experienced homelessness for a year or longer in Hamilton. I asked them about their experiences, and through art-based activities, about their ideas for housing and support.

What I learned in the interviews, combined with existing research, highlights a hidden crisis. Within our current system resides a profound human cost that manages, instead of resolves, homelessness.

Many women who experience homelessness do so for far longer than the federal government’s definition of chronic homelessness, which is six consecutive months or 18 months over three years. Research from the United Kingdom that focuses on long-term and unresolved homelessness for women found that the ways women experience homelessness is to “go around in circles” without having their housing or support needs met.

Among the women I spoke with, more than half had been experiencing homelessness for 10 years or longer. Six of the the women said they have never had a safe place of their own to live for the entirety of their adult lives.

All of the women who participated in this project accessed the services offered by the homeless serving sector, including shelters and outreach workers, designed to resolve their homelessness. Yet none of these women were able to have their housing and support needs met.

This means their experience of homelessness has persisted for years, and even decades.

Homelessness often starts in their teens

More than half of the participants I spoke with first experienced homelessness before they turned 18. Their primary route into youth homelessness was gender-based violence. They ran away from home when they were teenaged girls to escape violence and became caught in a cycle of events that include: hospitalization, incarceration, staying in youth shelters, living in group homes and unsafe places.

The Pan-Canadian Women’s Housing and Homelessness Survey, as well as a study on Toronto youth, echo what the women I spoke with told me. Studies from the United States also confirm similar patterns — homelessness begins early in life for a majority of women, and is often followed by a chronic, chaotic churn of precarious housing and homelessness situations.

The women in my study described a frustrating and exhausting cycle of going among institutions such as hospitals, jails, emergency shelters, drop-in programs and transitional housing programs. They had all spent periods of time living outdoors, in encampments, in motels, with unsafe people and in other precarious and temporary housing arrangements. This phenomena is well-documented in existing Canadian research.

Better definitions, better data

The Canadian government defines those who have been homeless and using shelters for more than 180 days a year as experiencing “acute chronicity.”

Another term used by the federal government for individuals who have accessed shelters at least once in each of the last three years is “prolonged instability.”

People who meet one or both of these criteria are considered to have the highest housing needs in the country.

According to recent federal data, women and gender-diverse people across Canada experience slightly higher rates of acute chronicity than men (13.4 per cent for men, 15.4 per cent for women, and 13.9 per cent for gender-diverse people). But the real numbers for women are likely much higher due to under-reporting.

Research shows women remain invisible to official systems during periods of homelessness. For example, the available data relies solely on information about emergency shelter usage. It does not capture experiences of homelessness that occur outside of the shelter system.

Women are less likely than their male counterparts to access shelters and other formal supports. Instead, they rely on precarious, unsafe and temporary housing arrangements to navigate homelessness.

In Canada, there are also fewer emergency women-specific shelter beds than for men

Rethinking responses to long-term homelessness

For the women I spoke with, the official 180 days or three years that makes someone officially chronically homeless in Canada does not even begin to describe the length and complexity of their experiences of homelessness.

They described wanting to live in supportive, gender-specific housing programs that foster community and care. Highly supportive housing typically integrates health and social services and a range of other support services. This type of integrated housing does exist across Canada — examples are the Block Line Supportive Housing Program operated by YWCA Kitchener-Waterloo and the Women’s Building (Alpha House) in Calgary — but there is not enough of it.

The current measurements from the government of Canada fall short of capturing the complexity of the homeless experience for many Canadian women.

Government officials must therefore not only rethink their definitions of those in the most housing need, they must develop responsive housing solutions to meet the needs of women who have been homeless for many years.![]()

Mary Vaccaro, Lecturer in Social Work, McMaster University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tuesday, April 29, 2025

Five ways to make cities more resilient to climate change

Climate breakdown poses immense threats to global economies, societies and ecosystems. Adapting to these impacts is urgent. But many cities and countries remain chronically unprepared in what the UN calls an “adaptation gap”.

Building climate resilience is notoriously difficult. Economic barriers limit investment in infrastructure and technology. Social inequities undermine the capacity of vulnerable populations to adapt. And inconsistent policies impede coordinated efforts across sectors and at scale.

My research looks at how cities can better cope with climate change. I have identified five ways to catalyse more effective – and ultimately more progressive – climate adaptation and resilience.

1. Don’t just ‘bounce back’ after a crisis

When wildfires, storms or floods hit, all too often governments prioritise rebuilding as rapidly as possible.

Though understandable, resilience doesn’t just entail coping with the effects of climate change. Instead of “bouncing back” to a pre-shock status, those in charge of responding need to encourage “bouncing forward”, creating places that are at less risk in the first place.

After the Christchurch earthquake in February 2011, the New Zealand authorities “built back better”, improving building codes and regulations and relocating vulnerable communities. Critics suggested reconstruction provided too much uncertainty and failed to acknowledge private property rights. But the rebuild did encourage better integration of planning policies and land use practices.

2. Informed by risk

It can be difficult to predict what the consequences of a crisis might be. Cities are complex, interconnected places. Transboundary risks – the consequences that ripple across a place – must be taken into account.

The best climate adaptation plans recognise that vulnerability varies across places, contexts and over time. The most effective are holistic: tailored to specific locations and every aspect of society.

Assessments must also consider both climatic and non-climatic features of risk. In 2015, in the UK, a flood affected one of Lancaster’s electrical substations, causing a city-wide power failure that took several days to rectify. In this instance, as with so many others, people had to deal not just with the direct impacts of flooding, but the ‘cascading’ or knock-on impacts of infrastructure damage.

Many existing assessments have limited scope. But others do acknowledge how ageing infrastructures and pressures to develop land to accommodate ever intensifying urban populations exacerbate urban flood risk. Others too, such as the recently published Cambridge climate risk plan, detail how climate risk intersects with the range of services provided by local government.

Systems thinking – an approach to problem-solving that views problems as part of wider, interconnected systems – can be applied to identify interdependencies with other drivers of change.

Good risk assessments will, for example, take note of demographics, age profiles and the socio-economic circumstances of neighbourhoods, enabling targeted support for particularly vulnerable communities. This can help ensure communities and systems adapt to evolving challenges as climate change intensifies, and as society evolves over time.

Complex though this might be, city leaders can access advice about improving risk assessments, including from the C40 network, a global coalition of 100 mayors committed to addressing climate change.

3. Transformative action

There is no such thing as a natural disaster. The effects of disasters including floods and earthquakes are influenced by pre-existing, often chronic, social and economic conditions such as poverty or poor housing.

Progressive climate resilience looks beyond the immediacy of shocks, attending to the underlying root causes of vulnerability and inequality. This ensures that society is not only better prepared to withstand adverse events in the future, but thrives in the face of uncertainty.

Progressive climate resilience therefore demands tailored responses depending on the population and place. In Bangladesh, for instance, communities are building floating gardens to grow crops during floods. These enhance food security and provide a sustainable livelihood option in flood-prone areas.

4. Collective approaches

Effective climate resilience demands collective action. Sometimes referred to as a “whole of society” response, this entails collaboration and shared responsibility to address the multifaceted challenges posed by a changing climate.

The most effective initiatives avoid self-protection, of people, buildings and cities alike, and consider both broader and longer-term risks. For instance, developments not at significant risk should still incorporate adaptation measures including rainwater harvesting or enhanced greening to lower a city’s climate risk profile and benefit local communities, neighbouring authorities and surrounding regions.

So, progressive resilience is connected, comprehensive and inclusive. Solidarity is key, leveraging resources to address common challenges and fostering a sense of shared purpose and mutual support.

5. Exploiting co-benefits

The most effective resilience projects exploit co-benefits – what the UN calls “multiple resilience dividends” – to leverage additional benefits across sectors and policies, reducing vulnerability to shocks while addressing other social and environmental challenges.

In northern Europe, for example, moorlands can be restored to retain water helping alleviate downstream flooding, but also to capture carbon and provide vital habitats for biodiversity.

In south-East Asia solar panels installed on reservoirs generate renewable energy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, while providing shade to reduce evaporation and conserve water resources during droughts.

In short, adaptation is obviously crucial for tackling climate change across the globe. But the real challenge is to deal with the impacts of climate change while simultaneously creating communities that are fairer, healthier, and better equipped to face any manner of future risks.

Don’t have time to read about climate change as much as you’d like?

Get a weekly roundup in your inbox instead. Every Wednesday, The Conversation’s environment editor writes Imagine, a short email that goes a little deeper into just one climate issue. Join the 40,000+ readers who’ve subscribed so far.![]()

Paul O'Hare, Lecturer in Human Geography and Urban Development, Manchester Metropolitan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.